The ability to reflect on one's cognitive processes facilitates systematic thinking and, naturally, learning. This is not a typical activity, although it is an essential practice in developing critical thinking — an abstract concept whose individual and collective benefits can prove very useful in organizations where a mistake can mean disaster.

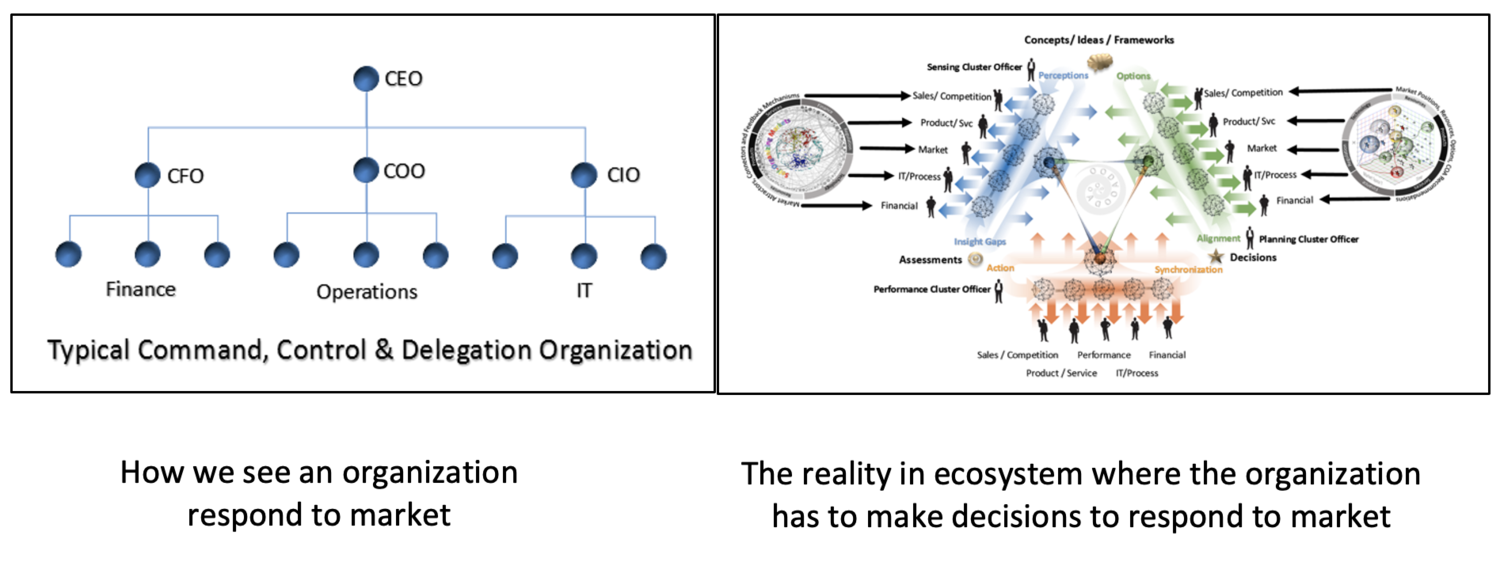

Paradoxes developed in Ancient Greece with logical premises and illogical conclusions already translated this will. Still, the military in the 50s created a tool, the O.O.D.A. Loop (Fig A), whose objective allowed it to justify solutions in unstable and ambiguous environments. Aviation, nuclear power stations, and offshore platforms were among the first activities to embrace this practice to increase agility and reduce the organizational and human error.

Searching for solutions in the error's reduction is associated with a need to build a straightforward narrative of events, whose meanings are revealed only after they manifest themselves. Structured critical thinking serves to guide scattered and disorganized events, give a narrative structure with purpose, answer problems, and reduce the margin of error.

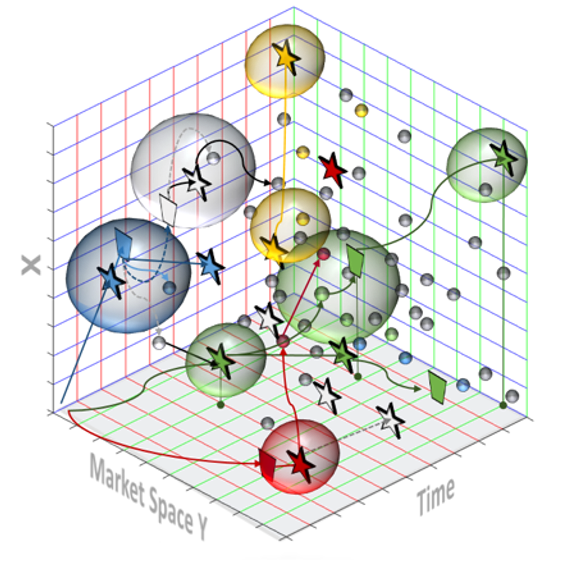

Figure B allows us to understand how we organize critical thinking using a permanent loop, evolving from the initial scattered information (chaos) to searching for patterns that reflect some meaning. When these patterns begin to interrelate and make sense, we develop our hypotheses and test the results. If we don't get the products or purpose, we will have to recognize the pattern's fallacy and restart the analysis again. If the ways make sense, we can think of a solution.

A look at daily events allows us to have an automatic answer to risks or ignore them, but few develop the habit of constructing meaning for these observations (an O.O.D.A.). Slight signs of an employee's emotional instability, the tool-impaired, standard response to an external request, absenteeism, stress, and emotional fatigue, or ignoring small safety rules are daily signs that can be devalued. To be alert means integrating the meaning of what is going on and foreseeing a timely solution to an already manifesting problem.

Individually, it isn't straightforward to evaluate or map the entire flow of information that surrounds us. Still, a team prepared in critical thinking and carrying a common goal can evaluate different events, consider solutions together, and build a narrative with potential solutions to present or future problems.

Critical thinking is ambiguous and uncertain — requiring space and time for learning — making its acceptance difficult to organizations. Errors, lapses, or breaches of security happen due to the way people see the environment and interpret the underlying action. It's not easy to continually assess these events correctly, so the team's ongoing support around us is crucial for this goal. This support is grounded in a culture with common rules and standards, a fluid network of contacts, trust, and credibility in responses.

Because the Agile mindset is focused on people — customers and employees — and products, critical thinking proves to be an essential source of innovative solutions and continuous improvement for products and services while seeking to understand people.

Using critical thinking in daily problems, bring them forward to teams without distrust, anticipating actions, make sense of potentially solutions and naturally shared the mistakes and successes when trying to solve those problems is what we expect from an Agile mindset.

This kind of culture is opposite to standards in colleges. In a course on Agile, I simulated a situation on the evolution of food business markets and their decision-making to buy or sell goods, providing data on price evolution, whether forecast and armed conflicts for them to analyze. Most of the students focused on buying or selling (gut feeling) and ignored the different analyses produced by colleagues. When I promote teams tasks for helping the investigations, the only concern was a search for a convergence path between them, ignoring other possible but unlikely solutions.

Collecting as much information as possible, asking for contributions to solving the problem, exploring and experimenting, simulating scenarios when there is little experience in the field, crediting solutions that do not imply winning or losing are meaningless actions for my students, but fundamental in Agile organizations.

Being able to promote critical thinking is vital in every organization but especially in those seeking Agile. Unfortunately, Human Resources at your company can identify employees' technical skills but don't know how to recognize non-technical skills, the common sense using in client's contact, team's coexistence, or the change evaluation in their work environment.

Soraia Jamal

Soraia Jamal is an Agile Consultant and Organizational Psychologist with 20 years of experience, specialized in Organizational Behaviour and Performance Optimisation.

Her vast experience in military and aviation sector, in particular with high performance crews, allow her to assess teams and unleash the individual and collective potential by supporting the optimization of their performance and well-being.

Soraia’s professional experience includes expertise in organizational culture assessments and performance optimization in military, non-profit and corporate environments, and multi-cultural and multi-country contexts.